The Kuisls – a Bavarian executioner dynasty

The unsavory truth about a profession drenched in myth

For picture info see website details

Grim and aloof, with hood and executioner’s sword – the profession of executioner is tainted like no other through legends and prejudices. In books and on TV he is nearly always depicted as a sword-swinging brute with a hood and broad shoulders. We never find out who these people really were. Fourteen of my ancestors were practitioners of this bloody trade, most of them in Schongau, Bavaria. My own trade being that of a writer, I have the opportunity to do away with a few of the most prevalent clichés and spruce up my family’s image a little. Against this background, let’s take a look at the hero of my novel and my forebear, Jakob Kuisl, who lived from 1612 to 1695 …

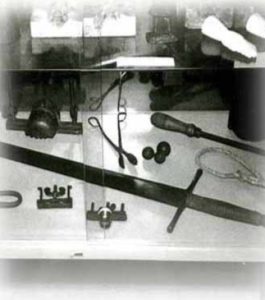

My ancestors’ original executioner’s sword, which was stolen from the Schongau town museum in the 1970s. It has not resurfaced to this day. For any information leading to the capture of the perpetrator I am offering the reward of a free reading and ten free signed copies of my book.

My ancestors’ original executioner’s sword, which was stolen from the Schongau town museum in the 1970s. It has not resurfaced to this day. For any information leading to the capture of the perpetrator I am offering the reward of a free reading and ten free signed copies of my book.

A bloody master’s examination

For picture info see website details

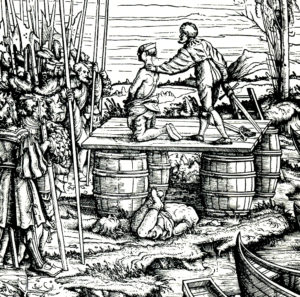

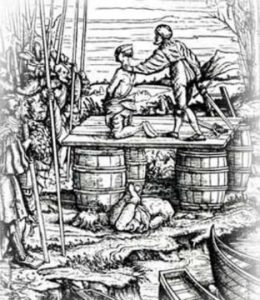

Like any other executioner in Germany, Jakob Kuisl served a hard apprenticeship that began when he was still a child. The job of executioner was usually passed down from father to son, whose duties as apprentice boy and assistant were initially limited to hanging and torturing. For beheading, Jakob first had to complete a professional master’s examination and cut off the head of a criminal in the prescribed manner under the eyes of the master who had trained him.

There still exists a master letter from the 18th century belonging to my forebear Johann Michael Kuisl in which his exemplary execution performance is certified. The letter confirms that “he completed his masterpiece in the presence of a large gathering with such skill and dexterity as to duly earn the position of executioner and be highly recommended for all further executions.”

There still exists a master letter from the 18th century belonging to my forebear Johann Michael Kuisl in which his exemplary execution performance is certified. The letter confirms that “he completed his masterpiece in the presence of a large gathering with such skill and dexterity as to duly earn the position of executioner and be highly recommended for all further executions.”

For picture info see website details

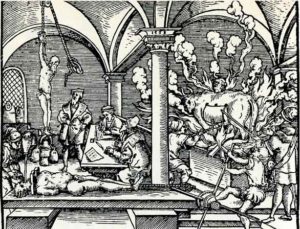

Beheading was seen as the punishment of honor among the many execution methods in the Middle Ages. It was reserved for noblemen and -women and young child murderesses. Beheading must have been very difficult, technically speaking, as it involved landing a single, precise blow of the sword between two vertebrae in the neck. To combat his fear and his stage fright (a crowd of thousands is watching with anticipation!), Jakob has an intemperate amount to drink before the executions. He then has difficulty staying upright and not staggering as he mounts the beheading station that he built himself.

His forebear Jörg Abriel once caused a veritable bloodbath when in a similar condition. An executioner from Nördlingen has it that he was so drunk he saw seven heads in place of the usual two. Accordingly, the execution ended in a massacre. Another time the executioner’s wife had to finish the job because her husband was in no condition to do so. A debacle such as this could have deadly consequences not only for the delinquent but for my forefather too. It often happened that a botched beheading was followed by the lynching of the executioner, who was left swinging from the nearest lime tree, adjacent to his beheading station. In Schwabmünchen in 1719, there was even an early case of mobbing when the executioner’s sharpened sword was maliciously replaced with a blunt one. The beheading failed and the executioner had to flee the town.

An outcast

For picture info see website details

As an executioner, Jakob Kuisl would have had a lonely life. His house was situated outside the town; at the inn he sat in a designated place and had his own tankard. When the executioner entered the pub room itself, he had to ask the permission of all those present before he could sit down. The Kuisls were not allowed to hold honorary office, marry in a church, or have their children baptized as Christians. A church burial was similarly denied them. Their profession, like that of the prostitute, the carny, the barber-surgeon, the shepherd, the bailiff, and the miller(!), was “dishonest.” This meant that they were also unable to change professions, never mind being allowed to marry someone from a different guild. This was among the reasons for the Kuisls becoming an executioner dynasty that lasted hundreds of years and extended over great swathes of Bavaria.

Garbage collector, torturer, and medical practitioner

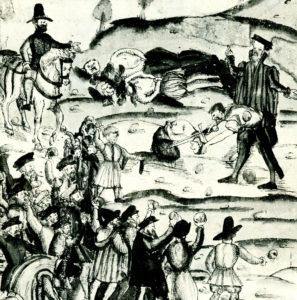

Executing alone was not sufficient for Jakob Kuisl to feed his five children. A lucrative beheading turned up once in a blue moon in these small towns, and so, like all executioners, Jakob also worked as a knacker. In this capacity he organized the removal of dead animals and was in essence the town’s garbage collector, removing trash and fecal matter from the streets. In larger towns, the executioner was also responsible for the local bordello and the gambling trade. And for torture, of course …

Jakob Kuisl charged 2 guldens and 30 kreutzers for “tormenting” (torturing) a witch, while cutting out a tongue cost 2 guldens and pinching with tongs 1 gulden and 8 kreutzers per pinch. Burning wasquite profitable (5 guldens), and breaking someone on the wheel even more so (9 guldens).

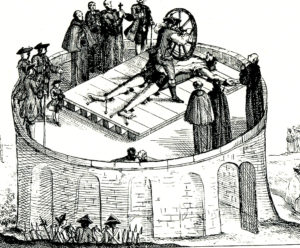

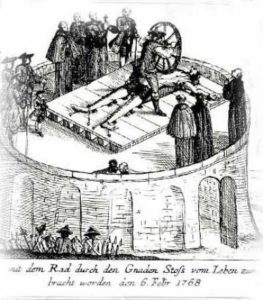

For picture info see website details

Breaking on the wheel was the cruelest form of execution. All of the condemned’s limbs were broken by means of a wheel or an iron bar. Thereafter he was tethered to the wheel and exhibited. The wrongdoer often remained alive for hours or even days. If there were mitigating circumstances, the executioner sometimes broke the victim’s neck. This is the origin of the expression coup de grâce.

But this was not enough to sustain Jakob’s family. Nearly half of the executioners’ income derived from practicing medicine. In German towns it was quite common for the sick to go to the executioner rather than the doctor (whom they could ill afford). We know that Jakob Kuisl had an apothecary’s cabinet in a chamber of the family home, stocked full of all sorts of crucibles, pots, and powders. Like many other executioners, he also had an extensive medical library. A big seller was the so-called “human fat” that he and his colleagues harvested from the bodies of the executed and sold to local apothecaries. This cream, used to combat rheumatism and consumption, was as popular as aloe vera is today.

Competition from doctors

For picture info see website details

There were two principal reasons for the executioners’ deep knowledge of medicine. First, they were free to study cadavers whenever they wished. Second, they were obliged to restore their torture victims to their original condition before executing them. Jakob Kuisl was therefore also a master in setting and splinting damaged limbs. With his medical expertise, the executioner was the natural competitor of the doctor, who was perpetually putting a spoke in the former’s wheel and reporting him to the authorities. My forebear, Munich knacker Johann Adam Kuisl, was renowned as a medical practitioner far beyond the walls of the city. Again and again, the local doctors had his books and medicines confiscated. Johann Adam Kuisl once spent a period of six weeks under arrest, about which his wife complained bitterly: “(My husband) … has often petitioned, and is ready at all times, to be publicly tested by the highly commendable collegium medicum in order to demonstrate that he could not be further removed from a (…) mere quack.” To no avail – in 1756 all executioners in Germany were banned once and for all from curing people and trading in medications. However, business continued under the counter, not just with medicine alone but with macabre talismans to boot. Pieces of gallows halter and gallows wood, a phalanx, or an entire thief’s thumb were valued lucky charms. As was the blood of the beheaded or the semen of the hanged. During the Thirty Years’ War, an executioner from Passau sold amulets of invulnerability (that didn’t work), and my famous forebear Jörg Abriel, at the time a genuine pop star among executioners, is reputed to have owned four books of magic. His daughter ran a brisk trade in talismans of all kinds. Incidentally, it was Jörg Abriel who dispatched dozens of witches during the famous Schongau witch trial of 1589. The executioner, himself a sorcerer – the irony of it all!

From pariah to respected physician

For my ancestors, secularization marked the final end to their executing ways. Torture was abolished and executions were centralized, performed henceforth only in the major cities. The Kuisls were forced to seek alternative employment. Many executioners switched to occupations that they already mastered. They became barbers, veterinarians, surgeons – and doctors.

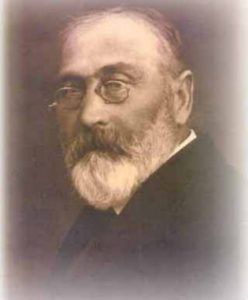

My great-great-grandfather Max Kuisl (1861 to 1924) ultimately achieved what had always been denied his forebear Jakob Kuisl: he made a career as a qualified, recognized physician.

My great-great-grandfather Max Kuisl (1861 to 1924) ultimately achieved what had always been denied his forebear Jakob Kuisl: he made a career as a qualified, recognized physician.

My great-grandmother Anna Kuisl (1895 to 1936), known as “d’Ani”, wrote plays in her youth and married a woodcarver. Her sister was one of the first women to attend the Munich Art Academy and her brother Eduard published books of fairy tales. It is said that even as executioners the Kuisls were quite artistic.

My great-grandmother Anna Kuisl (1895 to 1936), known as “d’Ani”, wrote plays in her youth and married a woodcarver. Her sister was one of the first women to attend the Munich Art Academy and her brother Eduard published books of fairy tales. It is said that even as executioners the Kuisls were quite artistic.

And so, after almost half a millennium, the Kuisls did actually make something of themselves.

Family tree